Understanding Behavioral Economics, Climate Change And The Sustainable Choice

The headlines circulated at the office this week included “Decline of Pollinators Poses Threat to World Food Supply” and “Arctic warming: Rapidly increasing temperatures are 'possibly catastrophic' for planet, climate scientist warns” . On social media, similar news is trending as awareness of the threats and risks of climate change grows - but is awareness enough?

Climate Change is paralleled by accelerating patterns of unsustainable consumption, whereby today we consume more resources than 1.5 Earths can provide. If this trend continues, these same estimates note that in about 30 years we will need more than two Earths to meet our consumption demand. Our current consumption behaviors are thus unsustainable.

Still, surveys estimate that some 2 billion consumers worldwide are still unaware about the threats that our unsustainable consumption and production patterns have fomented through climate change. In order to develop effective policies, voluntary measures, and partnerships that reverse these unsustainable trends, we must effect changes in consumption behaviors, because human actions are the prime causes of today's environmental outcomes. In our Anthropocene era , policies and international commitments such as the SDGs and the Paris Agreement must effect behavioural change.

In a span of four months in 2015, United Nations Member States achieved consensus adopting two potentially groundbreaking agreements that will hopefully change the course of these ominous headlines for humanity. A 15-year agenda was adopted with 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) titled “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, and the on the COP21 Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. However, while governments achieved consensus and the high-level intentions are there, can the consumers of today and tomorrow change the behaviors and social norms, which result in unsustainable use of resources, thus causing climate change? Better yet, can policymakers and business actors across countries and corporations change their decision-making processes to support these momentous agreements over the short and long-term?

The SDGs cannot be achieved without behavioral change. For example, by 2030, SDG 6 on the Sustainable management of water and sanitation for all aims to substantially increase water-use efficiency and ensure sustainable withdrawals of freshwater (Target 6.4). SDG 12, like many others, is especially rooted in changing behaviors and social norms to ensure sustainable consumption and production in our societies. Key targets of the goal aim to halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels; substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse; and even ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature.

In effect, all of the SDGs require changes in our decision and behaviors as consumers and producers to change our social norms on SDG topics as diverse as birth registration for all to ending the trafficking of protected species of flora and fauna. . Yet, behavior and social norms are not mentioned once in this complex agenda of 17 goals and 169 targets.

Social Science today has achieved greater knowledge on the complexity of how human decisions are made – the conclusion is that we are not rational actors. According to neoclassical economic assumptions, the human individual behaves rationally, with their decisions guided by principles of utility maximization. Rational choice theory is compelling and has proven useful for substantiating various economic theories. However, it falls short in explaining why people do not always act in their own interest with adverse behaviours such as pollution, overeating, smoking, or mounting consumer debt. In addition, it does not explain today’s well-known gap between the intentions and actions of consumers when it comes to climate change and sustainable consumption choices. For example, 72% of consumers surveyed in Europe say they are willing to buy green products, but only 17% actually do.

Research in fact shows that decisions are influenced by number of factors which are more irrational, including psychological factors, sometimes strongly associated with emotions, social context, habits and routines (Darnton, 2008). A behavioral lens can help solve this commonly observed intentions vs. actions gap to eventually guide consumers towards more sustainable livelihoods and lifestyle choices as well. Today, the field of Behavioural Economics combines disciplines of psychology, marketing, economics and other sciences to analyse, model, and predict behaviours and human choices more effectively. These behavioral insights can now be applied to ensure that policy frameworks can be made more effective in changing societal behaviors and eventually social norms – to truly deliver on the SDGs and Paris agreement.

Over the past decades, governments from the United Kingdom to Colombia are increasingly integrating behavioral insights to deliver more effective policies across a variety of governance areas – however the application of these to encourage pro-environmental behaviors is just getting started.

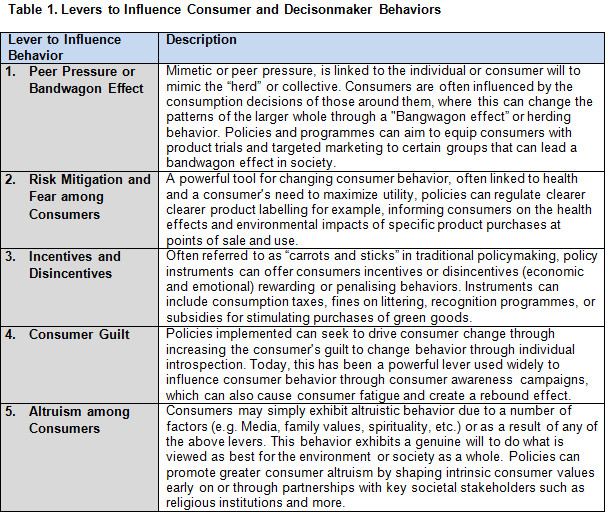

Research over the last decades on behavioral drivers has shed light on a series of core behavioral drivers or psycho-social "levers" to promote more sustainable behaviors. For example, a policy to ensure consumers reduce purchases of products linked to the extinction of a species and illegal trade on wildlife, such as elephant ivory, should push on one or multiple levers above to change social norms and purchasing patterns. If a definitive import ban on a product is not possible, then consumer demand can be shifted in other ways that change the behavioral drivers and decisionmaking process in the consumer. These levers collected in the summary table above can shed behavioral insights into the policy formulation process to change social norms in our societies today.