Extreme weather events, coupled with vulnerable and exposed socioeconomic systems, can lead to significant negative economic impacts, particularly in the agriculture sector (IPCC, 2014). These weather-related disasters are costly to prevent –and costly to recover from (UNISDR, 2015). Emphasis on the physical resistance of protection infrastructures has succeeded in reducing the vulnerability of exposed assets; yet, coupled with population growth, standard of living improvements in living standards and the resultant competition for land, hard engineering solutions have favored locating households and economic activities in potentially dangerous places. The compound effect of socioeconomic dynamics and the intensification of extreme weather events as a result of human-induced climate change has inflated risk and damages (IPCC, 2014). This is especially true for agriculture, which, because of its need for extensive stretches of land and its lower value per surface unit, is often shifted to riskier locations such as floodplains.

Damage recovery instruments offer financial compensation to those affected by disasters. For example, in large disasters where there is no legal liability, contingency funds (mostly through state aid) have traditionally played a major role. These funds are, however, very costly and distribute the burden of cost unequally. A different approach is therefore often advocated. In particular, renewed attention has been given to insurance arrangements that entitle policyholders to receive a compensation in exchange for a regular premium (EC, 2013a; OECD, 2015; UNISDR, 2015; WEF, 2016).

Insurance short-circuits the link between damages and losses, and eases post-disaster recovery. Compensations are addressed by establishing a capital fund based on actuarial assessment and the law of large numbers. Insurance systems with comprehensive coverage and uptake offer some advantages as compared to alternative damage compensation instruments: i) insurance is not restricted by a liability framework; ii) insurance removes uncertainty compensation and eligibility requirements (v. contingency funds); and iii) insurance is (at least partially) funded by policyholders, thus relieving pressure on the public budget (v. conventional public contingency funds/state aid).

Recent studies show that a 50% insurance coverage can reduce the impact on growth of extreme events with a large return period (250 years) by as much as 40% as compared to a situation without insurance –thus making disaster damages nearly inconsequential in terms of relinquished output (S&P, 2015a, 2015b). On the other hand, excessive reliance on public contingency funds may lead to downgrading national credit ratings, already vulnerable as a result of the Great Recession, to strengthening budgetary constraints and to limiting the capacity for disaster recovery. For example, a once-in-250-year tropical storm may downgrade sovereign credit-worthiness up to 2 notches in Bangladesh and 2.5 notches in the Dominican Republic (S&P, 2015a, 2015b). Furthermore, insurance mechanisms based on risk-based pricing introduce incentives for risk-mitigating behaviour (Surminski et al., 2015).

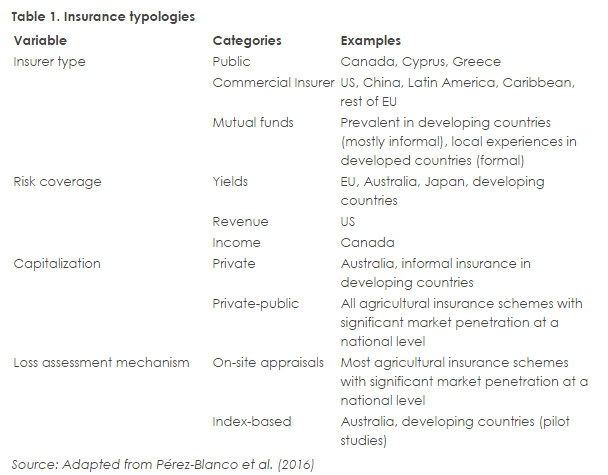

Agricultural insurance is a heterogeneous instrument, and can adopt different forms. In a recent book by FEEM researcher Dionisio Perez Blanco (Pérez-Blanco et al. 2016), these different forms are explored in detail (See Table 1). Agricultural insurance can be supplied by a commercial insurer (e.g. Australia), the public sector (Greece) or a group of farmers, through either a formal (mutual fund) or informal agreement (common in developing countries). Because of technical barriers, data constraints and capital restrictions (Kaminsky et al, 2012; Plantier, 2014), mutual funds and informal insurance arrangements among farmers are often the only real insurance alternative in developing countries. In developed countries, experiences with mutual funds have been traditionally limited to the local level; however, the new EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2014-2020 promotes the adoption of mutual funds to alleviate gaps in the development of crop insurance schemes and offers subsidies to help them capitalize and overcome technical barriers, and this may result in larger uptake (EC, 2013b). In the US, agricultural insurance typically addresses revenue (yields and output prices) (FCIC, 2014), while yield insurance prevails elsewhere.

However, despite these significant advantages, insurance is not a panacea. There is a long list of agricultural insurance schemes, and the adoption of one particular scheme and its effectiveness is conditioned by the existing risk management policy, site-specific factors (e.g. budgetary constraints, exposure, vulnerability) and institutional arrangements, which may lead to institutional lock-in situations, with undesirable outcomes. Climate change, along with population and economic growth, increases uncertainty and challenges traditional actuarial principles (the law of large numbers) that cannot be addressed by conventional actuarial tools. Uncertainty may result in higher damages and/or lower penetration rates, and demand additional public support. Budgetary constraints, in many cases aggravated by the financial crisis, demand a reformulation of current damage compensation systems and a transition towards more efficient schemes such as risk-based pricing insurance, as in the UK’s Flood Re. To sum up, the current momentum of insurance policies offers opportunities for improving risk resiliency, but caution is needed to transform these opportunities into tangible, genuine progress (Surminski et al., 2016).

This need has been noted by the scientific community, which has thoroughly investigated the preconditions for developing successful agricultural insurance schemes. The policy framework and the regulatory environment are key factors in bringing this about, but their wide variety makes the implementation of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ insurance scheme difficult. On the other hand, standardized methodologies have been consistently developed to provide increasingly accurate estimates of insurance premiums. Although uncertainty is an ongoing challenge to the validity of these models, substantial advances have been made. For example, many models already incorporate climate change simulations in their estimations of basic risk premiums. This helps to better inform the decisions of private and public agents. On the negative side, the study of the willingness to pay for income insurance still remains in an early stage, with major problems persisting (especially in developing countries). Since public subsidization is necessary to attain higher penetration rates at affordable prices, this gap complicates the task of the public sector and is a major problem in designing drought and crop insurance schemes.

This blog was originally posted on CarloCarraro.org, for full list of references see here.