The release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest report represents a “code red for humanity” – and for climate-vulnerable Indonesia. Having already pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2060, how can a country of 17,000 islands now implement change on the scale required? The answer – as Indonesia is learning – starts in the classroom.

As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest assessment on the state of our planet has grimly reminded us, change is urgently needed.

In 2020, government leaders around the world were quick to commit to change in the face of the socio-economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic – to “Build Back Better”, as part of a green recovery.

While we listened at the time, the evidence suggests that governments have done little to back up these statements. With only 2.5% of total recovery spending having been allocated to green initiatives, the trend has very much been a revert to “business-as-usual.”

But as the IPCC latest’s report has shown, “business-as-usual” is no longer a genuine pathway to survival. With the Paris Agreement’s less ambitious target of 2°C now on course to be breached by mid-century, we are sitting at a “code red for humanity.”

So the question now is – how do we catalyse change, before it is too late?

Accelerating Change

As well as being a “code red for humanity”, the IPCC’s latest report is a “code red” for Indonesia. Now one of the world’s fifty largest economies, it is also one of the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. An archipelago of over 17,000 islands, it is highly exposed to flooding and extreme heat, and its economy and labour market is strongly dependent on natural resources.

In 2017, Indonesia launched the Low Carbon Development Initiative (LCDI) with the goal of integrating climate action into the country’s development agenda. The LCDI aims to identify development policies that maintain economic growth and alleviate poverty while simultaneously helping the country to meet its climate objectives.

The LCDI now underpins Indonesia’s path towards a green economy and net zero emissions – which it has pledged to reach by 2060 – and therefore represents an aspiration for change on a transformational scale. However, such change does not just simply happen overnight. It is a process that must be driven by a corresponding, radical shift in collective mindsets, attitudes, and behaviours.

And as the IPCC acknowledged in its latest report, such change can be accelerated by two important tools.

Education and information.

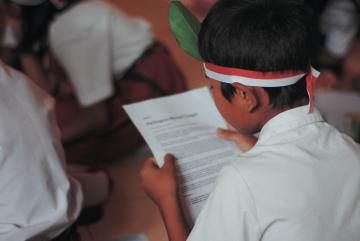

Educating to Survive

Access to climate information can help germinate a deep understanding of the challenges humanity is facing. In many cases this is evidently still lacking – both in Indonesia and beyond – and it is here that education and learning can play such a vital role.

By filling in these information gaps, education can drive the initial building and then transformation of knowledge and understanding into new behaviours and actions. A powerful catalyst for change, it can generate the human capital – skills, knowledge, competencies – needed to design and implement smart green policies (see the LCDI) that will avert climate breakdown.

Indonesia has embraced this. In 2019, the Indonesian government – with support from the Partnership for Action on Green Economy – conducted a Green Economy Learning Assessment (GELA) to identify learning gaps and entry points for advancing its green economy ambitions within the framework of the LCDI.

The GELA has now informed the development of an “agenda for change” in the shape of a concrete action plan that contains priority steps for building Indonesia’s green economy capacity. This will inform the development of a National Strategy for Green and Low Carbon Economy Learning, which will scale this process even further.

Learning for a Green Recovery

The findings of the GELA were presented in an international webinar held in June this year, on Learning and Skills Development for a Green Recovery. The webinar brought together speakers from the national government, development organizations, academia, workers associations and the private sector, and outlined a number of key steps for Indonesia to take forwards.

First, the GELA focused on the learning gaps, needs and priorities of government officials. While COVID-19 has highlighted the unique role that government’s must play in driving transformational change, they cannot carry the torch alone. Change must also be embraced, guided and monitored by a “green society”, and co-financed by the private sector.

Education and learning must mirror this. Capacity building activities are commonly segregated between sector and stakeholder groups, perpetuating the siloed mindsets that impede green economy progress. Green economy learning in Indonesia must therefore break these artificial barriers, and incorporate the perspectives of all – including workers, business and an increasingly active youth.

Second, it is widely acknowledged that while transformational change will generate new jobs, new business opportunities and new hope for many, there are many others that stand to immediately lose out. Achieving a “green society” will not be possible without incorporating the needs and priorities of these groups, and the notion of a “just transition” must be a central element of any such discussions.

This is particularly so in coal-dependent countries like Indonesia, where a green economy transition will significantly upend the socio-economic conditions of the 50,000 workers currently employed in the coal sector. Skills development – and particularly re-skilling – will therefore be vital in bringing these individuals on board, and ensuring that no one (and no worker) is left behind.

Change Today for Change Tomorrow

While Indonesia’s commitment to education and learning is an important step in reaching its green economy ambitions, and one that is now being matched in an increasing number of countries around the world (see recent examples in the Kyrgyz Republic, Kenya and Malawi), the dire warnings coming from the IPCC’s latest report highlight the fact that so much more work remains to be done.

While the recent Berlin Declaration on Education for Sustainable Development, which requires environmental education to be a core curriculum component by 2025, may suggest we are making moves in the right direction, other factors – such as the lack of climate change coverage in the recent reporting of extreme weather events across the world – should avert complacency.

Indeed, if we are to achieve the scale of change the IPCC’s latest report calls for, then we must continue to support education and learning as perhaps our last, great tool in the fight against climate collapse.

Otherwise, this latest report might be humanity’s final call.