Ever since the impacts of climate change have become evident in daily life, the question has arisen about the kind of social or economic consequences they could have. Among these, fiscal consequences have often been overlooked, despite their importance for investors and policymakers. Heller (2003) was among the first to recognize that climate change, through the damage it causes and its impacts on growth, can also be seen as a fiscal problem which in the long run poses serious obstacles to the sustainability of public finances.

The challenges of climate change and the policy actions to counter it will be as important in the coming decades as the aging of the population, terrorism or the globalization of today’s developing economies (Heller, 2003). And like these other challenges, climate change will have a significant impact on public deficit and debt.

To date, the literature and the attention of the international organizations have been mostly limited to the analysis of the fiscal effects of climate change and mitigation policies for achieving the 2 degree Celsius target, without considering the possible effects that adaptation policies might have. In addition, both climate change and the policies to combat it have always been analyzed and considered as a public expense. And if it weren’t? If we could see, in particular in adaptation policies, an opportunity to improve debt sustainability?

Adaptation expenditures (such as investments in infrastructure against rising sea levels or for protection from hydrological risk on fiscal sustainability), if properly evaluated and effective in preventing damage caused by climate change, can have a positive impact on future expenses (defined as post-disaster operating expenses) and can limit the loss of fiscal revenues (due to production loss).

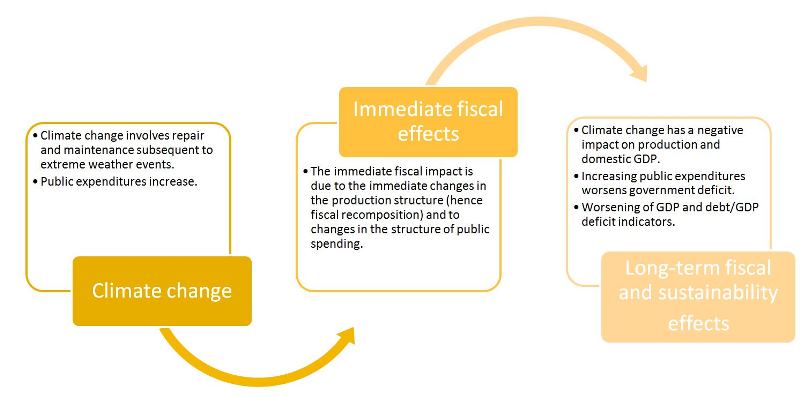

In the very definition of adaptation, these policies generate a positive cost/benefit ratio if compared to an initial situation where the economy is subjected to damage from climate change (Ekins and Speck, 2011). In this context, therefore, adaptation can have positive implications for long-term fiscal sustainability by simply avoiding the damage of inaction and by making the economy and society more resilient. The two options and their causality are highlighted in Box 1 below, in which a business-as-usual scenario (top) is compared to one of adaptation (bottom).

In this context, therefore, adaptation to climate change is not just a cost but also an opportunity for economies to improve their public debt sustainability through an upfront investment to protect the economy’s productive structure. The basic question is quite simple and intuitive: if our present-day economy invests money to protect itself from (potential) future damage caused by climate change, will it be able to improve its debt position as compared to a business-as-usual scenario?

This question is answered by the article “Climate change and adaptation. A new opportunity for public debt relief? “, presented July 9th at the “Our Common Future under Climate Change” conference in Paris during the session organized by FEEM, ICCG and the Global Climate Forum on “The Macroeconomic Opportunity of Climate Policy”.

Box 1 – The link between climate change and fiscal sustainability

The study seeks to analyze the medium term effects of an adaptation policy on hydrological instability in a group of Mediterranean EU countries (Italy, Greece, France, Spain and Portugal) with high debt levels (above the 60% established as a criterion for the Stability Pact), using a general equilibrium model (the ICES model).

This exercise compares two scenarios: the first is a climate change scenario in which each country is suffering from damage caused by hydrogeological instability; the second is a scenario of partial adaptation. In particular, it is assumed that the spending to limit the hydrogeological instability is compressed into the first five years, with much less residual damage than that actually suffered in the climate change scenario. But over time spending on adaptation loses its effectiveness and residual damage again increases. From this perspective, climate change is seen as an expense that a government must undertake, much like the concept of recovery spending.

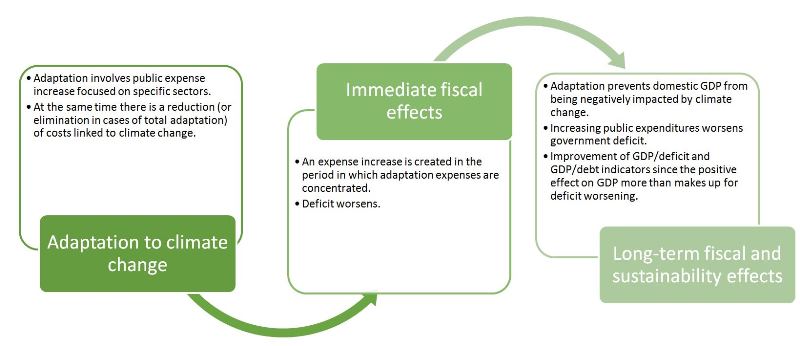

Chart 1 shows the different types of spending assumed for the two scenarios. In particular, in the case of climate change (with damage from hydrogeological instability), the expense is always on the increase throughout the period of reference (2007-2030), while in the case of adaptation the expense is broken down into two parts, a strictly “adaptation” one and another for “recovery” from residual damage. The first type of spending is concentrated in the first five years, during which time the total expenditure in the adaptation scenario is greater than the potential damage from hydrogeological instability, while subsequently the residual damage, though increasing, is less than the potential one.

In this first experiment, since the countries chosen have strong constraints on public spending due to high debt levels, it was assumed that the increased spending on adaptation is financed through the issuance of debt. This financing option is, among all, the least advantageous, because it forces the country to increase its stock of debt, with concomitant rises in its deficit levels, first from increased spending and subsequently from repayment of interest on the issued debt. Although in this case adaptation improves the fiscal indicators for these countries, the same indicators will be even better when the funds do not come from the issuance of debt but from other sources (taxes on carbon emissions, for example ).

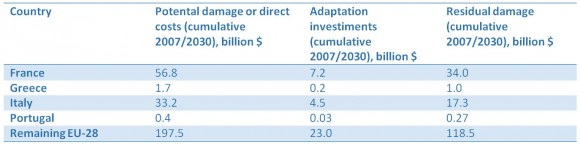

Graph 1 shows the percentage change in GDP between the two scenarios. During the expenditure period for adaptation, the GDP of the countries considered decreases because the added expense is financed by issuing debt that diverts resources from investment (crowding out effect), while subsequently the protective effects of adapation spending on the structure of production, and consequently on the country’s wealth, are reaffirmed, as in the standard analysis on climate change and adaptation. Especially for Italy and France, it seems that their GDP in recent years has been reduced in the scenario with adaptation rather than the one with climate change, since residual damage in the past few years has again begun to climb. In Greece and Portugal, however, residual damage has been nearly stable over time and roughly reduced by half compared to potential damage.

Graph 1 – The trend of GDP percentage change between the adaptation scenario and the climate change scenario

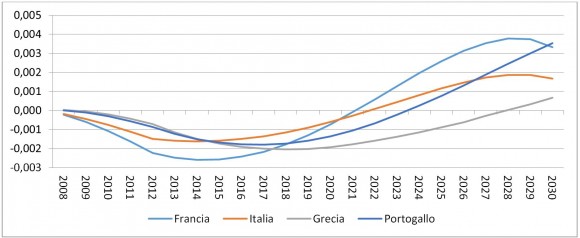

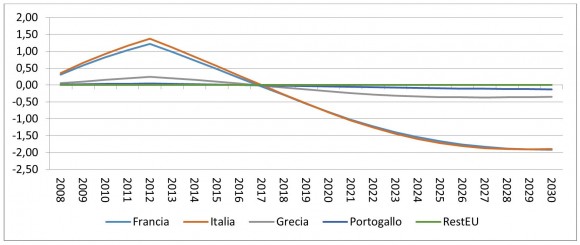

Charts 2 and 3 show the GDP/deficit and GDP/debt ratios. In both cases there is a deterioration of the ratio in the first five-year period, in concomitance with investment in adaptation. In that period, a deficit deterioration (due to increased expenses) combines with the worsening of GDP already noted in Chart 2. Subsequently, since the damage repair expense is greater than the adaptation investment, the government deficit is reduced and at the same time the country’s productive structure is “protected” from the negative impact of its hydrogeological instability. The variation in the size of the GDP/deficit ratio depends on the size of the incoming repair costs and the adaptation investments. France and Italy, according to the Lis-Flood (FP7 ClimateCost) model data, are the two countries with the highest investments for adaptation to hydrogeological instability (7.2 and 4.5 billion dollars, respectively); Greece and Portugal, however, must invest smaller amounts of money (0.2 and 0.03 billion dollars).

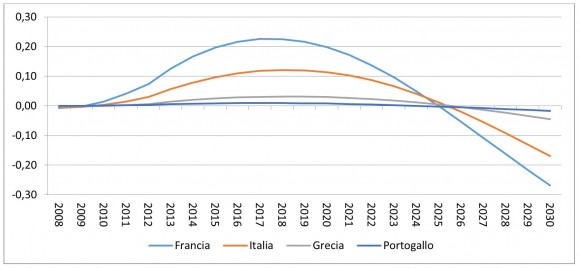

The trend in the GDP/debt ratio is very similar to that of the GDP/deficit ratio respectively. Again, in the medium term the positive effect on GDP of investment against hydrogeological instability leads to an improvement of the GDP/debt ratio despite the fact that the funding source postulated (deficit spending) is the least favorable one. The time profile in relation to the GDP/deficit ratio is somewhat different. The negative effect of the deficit increase is not immediate but put off till a later time. During the expense phase (2008/2013), we witness an initial worsening of the GDP/debt ratio, which however reaches its peak about five years later. This effect is mainly caused by having to pay interest to public debt holders. In a first period there prevails the negative effect of this expenditure increase, while thereafter both the deficit reduction and the GDP increase enable this ratio to improve as compared to the scenario with only the hydrogeological instability damage. The oscillations are however much more limited (+/- 0.3%) than in the case of the GDP/deficit ratio, which indicates a greater rigidity in the debt stock with respect to the adaptation investments, especially if one compares the annual deficit and the previous debt stock, which for these countries is especially important.

Graph 2 – The trend of percentage change in the GDP/deficit ratio between the adaptation scenario and the climate change scenario

Graph 3 – The trend of percentage change in the GDP/debt ratio between the adaptation scenario and the climate change scenario

The results of Bosello and Delpiazzo’s study (2015), which I have just described, are a first quantitative experiment for evaluating the fiscal consequences of adaptation policies. They nonetheless suggest an important conclusion: at least in the case of hydrogeological instability, investment spending for adaptation to climate change appears to be a strategy that allows us to reach a development goal without compromising the stability of the public finances. On the contrary.

The quantification of the damage from hydrogeological instability and the expenditures to avoid it, the method of financing investments and the distribution of these investments over time are the basic conditions for planning the best strategy for confronting climate change and ensuring that a expenditure policy can be the right tool for helping even the most indebted countries along the road to fiscal sustainability of their public debt.

Bibliography

Bosello F. and Delpiazzo E. (2015). Climate change and adaptation. A new opportunity for public debt relief? Presentation at the International Conference “Our Common Future under Climate Change”, Parigi, 9 luglio

Ekins P. and Speck S. (2011). The Fiscal Implications of Climate Change and its Policy Responses. Additional guidance supporting UNEP’s MCA4climate initiative: A practical framework for planning pro-development climate policies. UCL Energy Institute and UNEP.

Heller P. (2003). Who will pay? Coping with Aging Societies, Climate Change, and Other Long-Term Fiscal Challenges. International Monetary Fund.

IMF (2008). The Fiscal Implication of Climate Change. Fiscal Affairs Department International Monetary Fund

This blog awas originally published on the ICCG's 'Director Carlo Carraro's blog'.