As many as one million animal and plants species are currently threatened with extinction because of the impact of human activity, warns a recent United Nations assessment. It is no wonder, then, that this month British politicians declared an environment and climate emergency. The motion, while not legally binding, demonstrates the will of Parliament. It followed widespread, peaceful disruption in London, from the “extinction rebellion”, an international movement that, in its words, “uses non-violent civil disobedience to achieve radical change in order to minimize the risk of extinction and ecological collapse”. While in recent weeks Greta Thunberg, a 16-year-old Swede, inspired the mobilization of over a million schoolchildren across the globe to go on “strike” in the cause of climate change.

Actions like these – international and collective – are needed to make the transition to a more sustainable world a reality. But these efforts, wherever they happen, are often fraught with challenges – from competing political and commercial self-interest, to inertia in the face of what can seem like an insurmountable global challenge.

We believe the financial sector has a crucial role to encourage and stimulate others to take the right steps to tackle climate change. After all, the decisions a financial institution makes about who it lends to and invests in can dictate the impact it makes on the wider world. We believe money can be a force of good.

Increasing momentum for change

There are about 25,000 banks worldwide. But how responsible are they? How does their concept of responsibility compare to the people who are impacted by their financial decisions? While a few are advancing quickly in their sustainable impact, others are only at the cusp of understanding and integrating environmental sustainability or social purpose.

So, change in the banking sector is also necessary. The momentum for this is widespread. Customers and stakeholders expect banks to help make this worldwide shift. They are demanding genuinely sustainable financial institutions that are a part of the solution, not part of the problem.

On top of that, a coalition of 34 central banks and supervisors – the Network for Greening Financial Services – has recently issued a report highlighting the existential threat that climate change poses to the financial system. Writing in an open letter that calls for more collaboration between nations on the issue, the heads of the French and UK central banks warned that if some companies and industries fail to adjust to this new world, they will fail to exist.

Decarbonizing the economy

What can banks in practice do to help the transition to a sustainable economy? One of the biggest impacts the sector can have is to help decarbonize the economy to limit global warming to 1.5°C. That’s why an initiative announced by a group of leading Dutch financial institutions, during the 2015 Paris Climate Change Summit, is so important. These institutions, led by Dutch bank ASN, called on negotiators to take on board the role that investors and financial institutions can play to deliver the radical shift needed for a low-carbon economy.

More practically, the group committed to create a more transparent approach to assessing the greenhouse gas emissions of their loans and investments, for stakeholders inside and outside the Dutch financial industry. As such, the group created the Platform for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF). It was the world’s first effort of its kind by the financial industry for the financial industry. And it succeeded.

Until recently many financial institutions, and businesses more widely, considered reducing the carbon footprint of their own operations as enough to meet their environmental obligations. Behaving responsibly as an institution, through the choices each one makes about how to reduce energy use, source energy sustainably and limit business travel, for example, is important. But it plays a relatively insignificant role in the overall footprint of most financial institutions.

But why go to all this trouble? Accounting for the carbon emissions of loans and investments creates many and varied benefits for the institutions that do it. Banks, and the sector more broadly, can monitor their greenhouse gas emissions, create opportunities for comparison between institutions, and be more accountable and transparent to their stakeholders. Ultimately, they can use this information to set climate targets and steer investments towards a low-carbon economy. This will become possible next year when a project to create a methodology to set science based-targets for financial institutions concludes. This methodology, which already exists for many other sectors, will allow financial institutions to create a clearly defined pathway that specifies how much and how quickly they need to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to meet the Paris climate goals. The members of PCAF are co-sponsors of this work and closely connected to its development because they believe that banks should play their part in the transition to a low-carbon economy of the future.

Method in the madness

The PCAF methodology requires institutions to account for the footprint of their own emissions. It’s important to show stakeholders that they are “walking the talk” while recognizing that in most cases the contribution of their operation’s footprint to their overall emissions, will be relatively small. And it aligns with wider initiatives in the industry, such as the UN Principles for Responsible Banking, which aim to “accelerate the banking industry’s contribution to achieving society’s goals as expressed in the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Climate Agreement”.

Important frameworks like these demand exploring what financial institutions can do to make the biggest difference to serve society, target-setting and accountability; all of which, in the climate change realm, benefit from accounting for an institution’s greenhouse gas emissions. They also require a responsible approach if they’re to succeed. They should be linked to balance sheets and financial performance, including risk assessments. And it should be clear to stakeholders that this is only one part of the sustainability story; many important environmental and social issues are not directly covered by greenhouse gas emission accounting, such as biodiversity, water use, health, etc.

And, crucially, all data should be in service of an organization’s wider purpose and ultimately for society’s benefit. For example, a rigid interpretation of carbon accounting data might prompt an organization to only finance mortgages for “green” homes with a very high environmental performance. But most people don’t live in these homes. Instead, a financial institution could target homes with a higher carbon footprint, but offer products that incentivize making improvements to existing housing stock. Triodos Bank does just that by offering mortgages that link lower interest rates to higher environmental standards.

A case in point and what it taught us

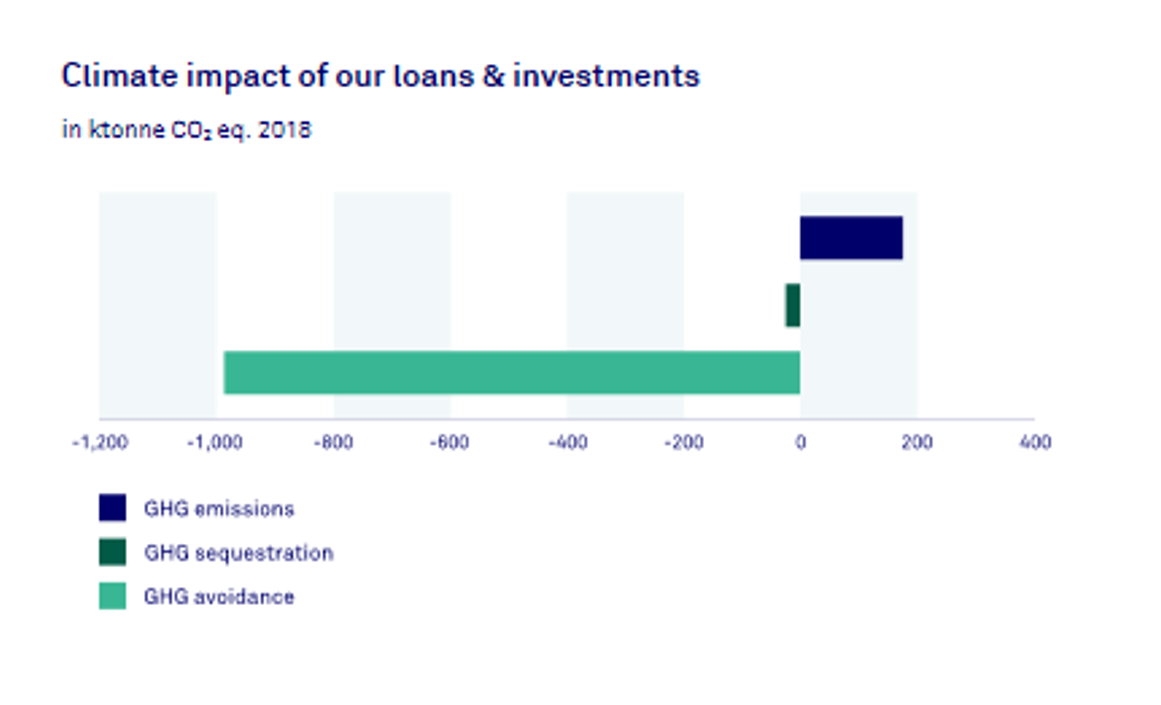

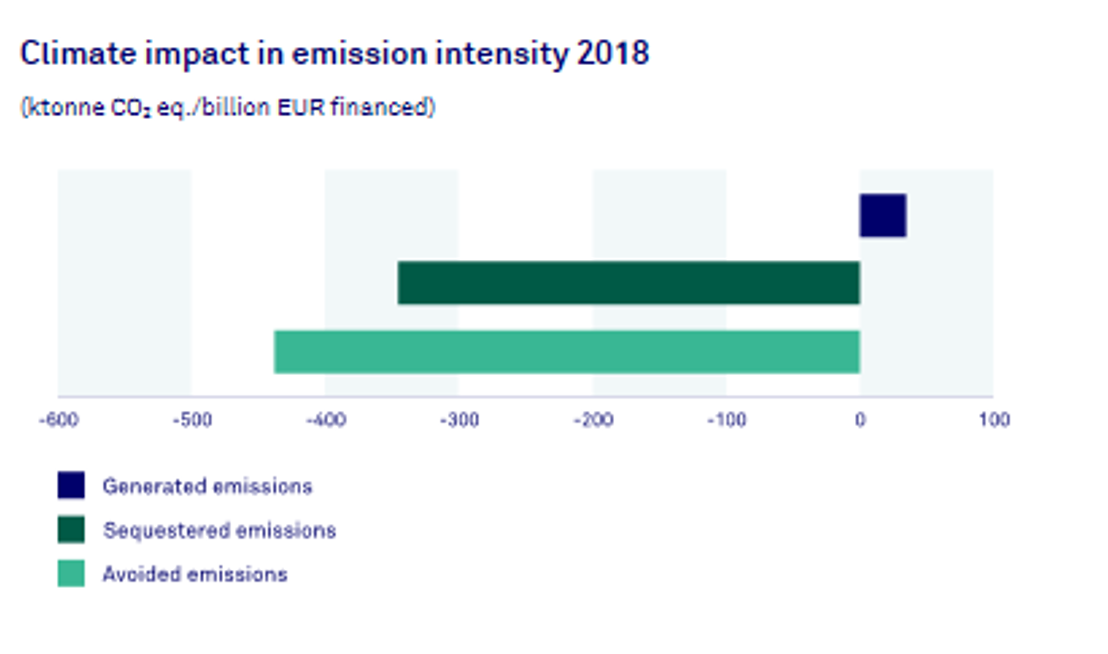

If we take Triodos Bank as an example, assessing the absolute emissions is a crucial starting point to understand what the bank’s commitment to only finance sustainable sectors adds up to in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. Triodos Bank did this for the first time in 2018 and these first, and early, results already show that financing a sustainable economy for many years has resulted in substantial avoided emissions and relatively low generated (or actual) and sequestered (or “absorbed”) emissions.

The actual emissions provide a baseline, which means the bank can start to improve and monitor the progress in working with customers to reduce emissions. The level of sequestered emissions provides insight on how to reduce emissions in the future, effectively “cancelling out” generated emissions.

The results show what financial decisions make the most impact in relation to the generated emissions, sequestered (or absorbed emissions, like forestry projects) and avoided emissions (such as green energy generated from renewable energy projects) of the companies Triodos Bank finances. The graph below highlights these “intensity” figures. In essence, they illustrate the greenhouse gas emissions per euro invested by Triodos Bank.

It’s important to develop harmonized ways to report on the results of this work and we are collaborating with other financial institutions to do that. Stakeholders should be confident in the information they see and be able to make fair comparisons between the footprint of different institutions. They should also know what this information does not tell them. For example, avoided emissions and generated emissions cannot, and should not, be presented to give the impression that they cancel each other out, leaving a “net neutral” situation.

A farm’s activities, for example, release greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, while green energy generated by a solar project avoids the need for energy produced from carbon-intensive fossil fuel sources. But the solar project does not remove the farm’s greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, in this example. They remain. And, unless they are removed by a carbon sink – such as a new forestry project – they will contribute to global warming for a long time. The solar project should, in time, replace the need for energy from fossil fuels, but they do not cancel emissions out. Given that we only have a finite amount of carbon that can be emitted into the atmosphere before the temperature goes above 1.5°C, these distinctions matter.

Accounting for carbon emissions globally through the GABV

Carbon accounting needs to be adopted by financial institutions around the world if we are to achieve the biggest impact. This is where the Global Alliance for Banking on Values plays a vital role.

The growth of this network of values-based banks is another sign that financial institutions are increasingly aware that money can be used for positive change. Our members have one thing in common: a shared mission to use finance to deliver sustainable economic, social and environmental development, with a focus on helping individuals fulfil their potential and build stronger communities.

At the moment, the GABV consists of 55 financial institutions and seven strategic partners operating in countries across Asia, Africa, Australia, Latin America, North America and Europe. Collectively, we serve more than 50 million customers, hold up to $197.6 billion of combined assets under management and are supported by close to 67,000 co-workers.

We want to ensure that banking is a healthy and productive system of society and develop a positive, viable alternative to the current banking system. We know that only by changing finance are we able to finance change. Increasingly, people are becoming aware of the interdependence of the real economy, social cohesion and our natural ecosystem, something values-based bankers have long understood, and which is at the heart of the business model. Knowing that people want to support positive change in society, we have an opportunity to demonstrate a healthy transformation of our sector, contribute to societal solutions and become a reference point for others along the way.

Amalgamated Bank, which is a fellow member of the GABV, has brought North American-based financial institutions together to adapt the PCAF methodology to the North American context. They expect to report on their work in the second half of 2019 and are playing a leading role in efforts to globalize the PCAF further.

GABV members, led by Triodos Bank and Amalgamated Bank, joined efforts to collaborate and bring carbon accounting to banks operating across the world. This work resulted in 28 members of the GABV committing to assess and disclose their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions within three years. The commitment, from members with combined assets of over $150 billion, means carbon accounting, using the PCAF methodology, will become global within three years, in Asia, Africa and Latin America as well as Europe and North America.

These developments have also been the catalyst for much wider efforts internationally to build a programme to attract conventional as well as more sustainable banks and other financial institutions to start carbon accounting. Several national, European and global initiatives help banks on their journey towards taking sustainability more into account. One way to generalize the PCAF method further across the mainstream are by adhering to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Banking. In September 2019, 130 banks signed this global initiative for the banking sector. It calls for specific targets to be set, based upon understanding the most significant impacts. In our view, the PCAF can help to achieve that goal.

Fundamental questions

Ultimately, this movement surrounding carbon accounting will enable participating banks to make financial decisions that limit the impact of the emissions of their financed assets so they can keep their contribution within safe environmental levels. By acting now, institutions may well be ahead of what will become requirements in the future. Recent statements about the existential threat of climate change, from regulators and supervisors referenced above, show how seriously this is being taken.

The power of this work to date is, in part, because it has been led by the industry – by individuals and organizations that want to do the right thing and have found a concrete way to do it. Carbon accounting is a starting point to manage emissions and address an institution’s climate impact. It is not the whole answer to this challenge in itself, but it is the foundation to make that happen.

The PCAF initiative reflects a genuine will to address a fundamental question about the positive role that business and banks, in particular, can play in safeguarding the well-being of future generations. It forces individuals and institutions to consider the purpose of an organization in its broadest sense, beyond financial return. It’s a sentiment that could resonate with schoolchildren inspired to take to the streets, politicians declaring a climate emergency and central bankers warning of the catastrophic impact of climate change to business as much as society. And it could hardly be more urgent.