A UN policy brief, Enabling Sustainable Lifestyles in a Climate Emergency, offers a number of approaches for local and national governments to address overconsumption and facilitate more sustainable lifestyles.

We are facing a triple planetary crisis and our lifestyle decisions are putting our earth further at risk. About two-thirds of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions can be attributed to households’ consumption and lifestyles. According to the latest report of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) focusing on mitigation, climate change is already affecting every corner of the globe and we urgently need to halve these GHG emissions. By addressing the demand side, there is a potential to reduce our emissions in end-use sectors by 40-70% by 2050.

The magnitude and speed of necessary cuts in greenhouse gas emissions require significant and rapid changes in predominant lifestyles, especially in high-consuming societies. Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, limiting global warming to 1.5C° and overcoming the triple planetary crisis – climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss – may be beyond reach.

Policymakers, however, have the power to change the context in which individual decisions are made. By intervening in key sectors and altering the default choices to align with sustainable lifestyles for all, governments can speed up emission cuts.

Outsized lifestyles

Research on the environmental impacts of consumption consistently finds that four domains are the most critical for environmental sustainability: food, housing, transport, and consumption of goods and services. The composition of the average carbon footprint by domains of consumption for 10 countries analysed in the 1.5-Degree Lifestyles report confirms the significance of these lifestyle domains.

Figure 1. Average lifestyle carbon footprints and breakdown between consumption domains for selected countries.

Source: 1.5 degree lifestyles: Towards A Fair Consumption Space for All, Hot or Cool Institute, 2021

The lifestyles of the wealthiest 10% of the world’s population (broadly speaking, most of the middle-class population in industrialized countries) are responsible for almost half of global emissions, while the lifestyles of the wealthiest 1% are responsible for about twice as many GHG emissions as the poorest 50%.

Figure 2. Per capita and absolute CO2 consumption emissions by four global income groups in 2015.

Source: Emissions Gap Report 2020, UNEP, 2020

One way to address these enormous inequalities between and within countries while reducing the global carbon footprint is to look carefully at what shapes our lifestyles, and how we can replace harmful options with more sustainable and desirable ones while ensuring that the poorest and most vulnerable groups in society are not negatively impacted.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) policy brief Enabling Sustainable Lifestyles in a Climate Emergency offers a policy perspective on how to tackle household emissions by facilitating the access to sustainable lifestyles, making it a useful guide for governments committed to action.

How can policies enable sustainable lifestyles?

Lifestyles encompass much more than just consumer spending and the use of consumer goods; they also include non-economic aspects of our lives. All of these activities have the potential to influence health and life satisfaction, as well as carbon footprints, directly or indirectly. There are three main factors shaping lifestyles and consumption: attitudes reflect intention, such as pro- sustainability behaviour or lack thereof; facilitators are enablers, which translate intention into action; and infrastructure shapes behavioural patterns or lock-ins.

Significant changes in lifestyles are more likely to happen when these three factors are addressed and work in conjunction with each other to reinforce sustainability.

Governments must ensure that policies lead to overall well-being for individuals, society and the planet. This requires bringing lifestyles within a fair consumption space, meaning that overconsumers will need to reduce their consumption to within biophysical limits, and those struggling may need to raise their consumption to meet their basic needs.

A common practice in public policy is choice editing. For example, in many countries, hard drugs and smoking in public places are prohibited, and seatbelts are mandated for car drivers. In essence, it is about editing out the harmful and carbon-intensive consumption options from the market, editing in the sustainable product and service alternatives to existing options while ensuring equitable access for all. A key aspect of successful choice editing in this context is creating a system that allows for better choices for people and planet without disadvantaging poorer segments of society and vulnerable groups.

A framework for shaping sustainable lifestyles

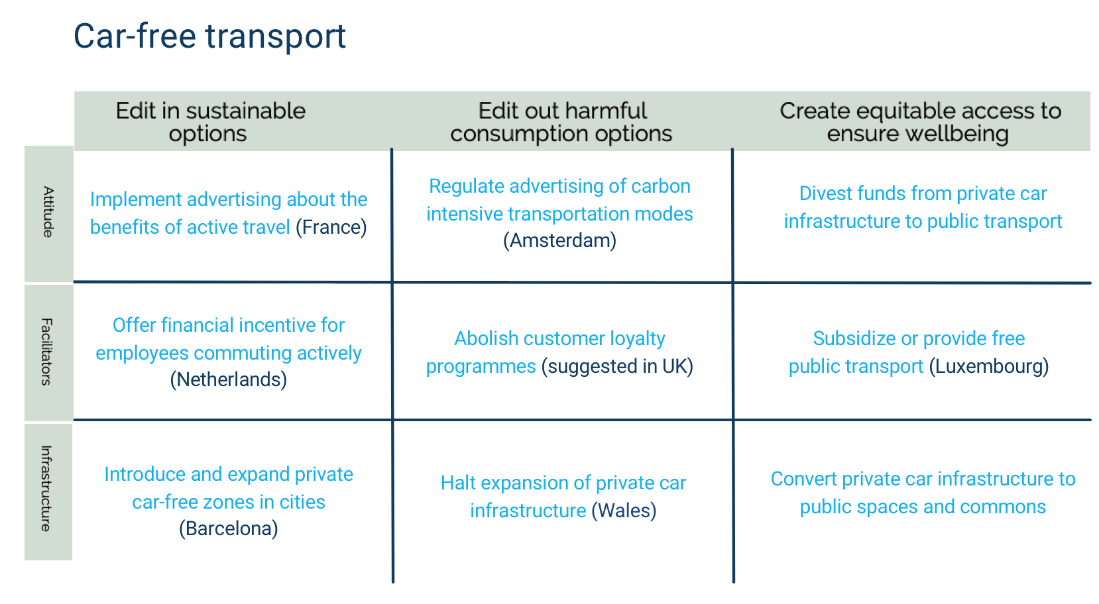

Using the Attitude-Facilitator-Infrastructure (AFI) framework and the choice editing approach, the policy brief addresses four lifestyle hotspots: food, transport, housing, and fashion. It provides real policy ideas for local and national governments. Most of the policies recommended have already been implemented around the world, making this brief an actionable tool for policymakers.

In most high-income countries, personal transport is the lifestyle domain with the largest contribution to the overall lifestyle footprint. The latest IPCC report estimates that there is a 6.5 GtCO2eq mitigation potential for land transport if the demand side is addressed. As for commercial aviation, while being responsible for a much smaller share of global GHG emissions, with 1% of the population responsible for 50% of the emissions, flying is one of the most inequitable areas of consumption. Figure 3 shows a few sample policies from the brief that together have the potential to support the move away from intensive car use towards more active and shared mobility, particularly in cities.

Figure 3. Reducing car dependence and carbon-intensive long-distance transportation – examples of actions.

By focusing on demand-side interventions, we cannot only reduce global emissions but move away from consumer-scapegoating and towards holistic, systemic actions. The joint framework proposed by the brief gives policymakers a series of paths to address the reduction of household emissions while also tackling inequalities.

Sustainable living for all is the baseline we should be using as we take action to address our triple planetary crises – climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss.