An alarming global employment situation

Almost 202 million people were unemployed in 2013 accordingly to the latest Global Employment Trends published by the International Labour Organization. Short term prospects are not bright either. Global unemployment is set to worsen with more than 215 million jobseekers by 2018. The youth unemployment rate at 13.1 per cent is almost three times as high as the adult unemployment rate – reaching a historical peak. This is particularly worrisome when noting that for Sub-Saharan Africa only, eleven million youth are expected to enter the labour market every year for the next decade.

In such a context, and not surprisingly, consultations aiming to define a global development agenda post-2015 – when the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) will come to an end – have seen employment issues high on the agenda. The “MY World” Global consultations on the post-2015 development agenda ranked better jobs opportunities as the third most important issue to people, after a good education and better health care.

One may say people just want jobs, no matter the colour. However, a deeper look at the current employment situation reveals that it is not just about the number of jobs. The quality of employment matters as much.

Vulnerable employment – that is, either self-employment or work by contributing family workers, – accounted for almost 48 per cent of total employment in 2013. This is five times higher than during the years prior to the crisis. Persons in vulnerable employment are more likely than wage and salaried workers to have limited or no access to social security or secure income.

In addition, the so-called “working poor”, that is workers living on less than US$2 per day, still account for 839 million workers (or 26.7 per cent of total employment). Although declining, the reduction happens at a slower pace than during previous decades. Finally, informal employment remains widespread in most developing countries reaching up to 90 per cent of total employment in some countries and regions (ILO, 2014).

As the World Development Report 2013 titled “Jobs” puts it, “it is not just the number of jobs that matter – some do more for development than others”. This includes jobs that make cities function better, connect the economy to global markets, protect the environment, foster trust and civic engagement, or reduce poverty.

Will green growth change this picture?

Now, how will green growth change this situation where even strong economic growth rates in Africa and elsewhere fail to deliver productive employment able to lift the majority of people out of poverty? What guarantee is there that going green will lead to jobs in higher number and better quality? What is the evidence from research and national experiences?

The most straightforward answer to these questions could just be a “yes, but…” Indeed, there is emerging evidence that greener economies may offer better employment outcomes but there are conditions for that to happen.

There is emerging evidence that greener economies create jobs

In general, studies suggest that a shift to a greener economy creates additional employment in a range of sectors. The ILO report “Working towards sustainable development” reviewed nearly 20 studies most of which indicate a net employment gain in the order of 0.5–2 per cent, which would translate into 15–60 million additional jobs globally.

This is corroborated by figures on job creation in many countries and sectors. Germany created 250,000 jobs as a result of its ecological tax reform over the period 1999–2003, particularly in labour-intensive sectors, while reducing fuel consumption by 7 per cent and CO2 emissions by 2–2.5 per cent.

In the United States, 2.7 million jobs have been created in the “clean economy” industry in, mostly among low- and middle-skilled workers, in the largest US metropolitan areas.

In China, over 1.7 million people are currently employed in the renewable energy sector and 6.8 million direct and indirect jobs could be created by meeting government wind, solar and hydropower targets.

In total, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that over 5.7 million people were employed directly or indirectly in the renewable energy industry in 2012 – a figure that could triple by 2030.

However, employment gains are by design, not by default

Such employment gains, however, do not occur by default, but rather by design. They result from a mix of policy and investment decisions which are very much country-and-context-specific. Policies must set job creation as a goal in itself, not just assumed to be an immediate consequence of growth – even when it is labelled green growth.

A variety of policies are being deployed in countries across the world. The main policies which could drive a job-rich transformation to greener economies are:

- macroeconomic policies, aimed at redirecting consumption and investment through price signals and incentives for enterprises, consumers and investors, including taxation, price guarantees, subsidies, finance and public investment;

- sectoral policies for key economic sectors or important groups of enterprises, in particular SMEs. This includes most environmental regulation as well as mandates (such as the share of renewable energy in power supply, energy efficiency standards, or biodiversity set-asides in agriculture and forestry); and

- social and labour policies, which ideally include a combination of social protection, employment, skills development and active labour market policies.

Building the skills for green jobs is essential

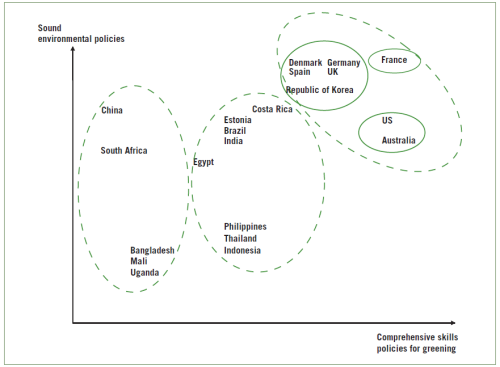

Of particular importance is the building and upgrading of skills for green jobs. The transition to a greener economy requires new skills both for new occupations as well as for transformed occupations. An ILO review of 21 countries revealed that skills gaps and shortages are already recognized as a major bottleneck in a number of sectors, such as renewable energy, energy and resource efficiency, renovation of buildings, construction, environmental services and manufacturing.

Source: ILO, 2011, Skills for green jobs: A global view

Companies investing in new technologies need to be able to find workers with the right skills. This implies that countries need strategies that align their energy, environment, education and skills development objectives and policies leading to programmes for potential skills upgrading and the redesigning of national vocational training and education schemes.

Not all winners – a few may suffer

It is important to bear in mind that shifting to a greener economy will not occur without some loss of employment, at least for certain specific economic sectors. In the industrialized countries, it is estimated that about 1 per cent of the workforce is likely to be affected by the transition between sectors of the economy. The labour markets impacts are thus minimal, except for certain energy-and-carbon-intensive industries, which in all cases are not large employers in the first place.

More research and understanding is needed on how green growth might affect different categories of workers and the distributional impact across society. This points to the importance of social protection and social safeguards.

For green growth to enhance social inclusion, dedicated social and labour market policies will need to complement economic and environmental policies. Several countries have tried innovative social protection mechanisms and conditional cash transfers, allowing communities affected by greening policies to find alternative sources of livelihood and low-skilled workers to secure an income.

For example, the Brazilian Bolsa Verde (green grant) programme includes a green grant designed to provide incentives to poor families living in natural reserve areas to engage in environmental conservation. In its first year Bolsa Verde provided monthly payments of about US$35 each to about 16,634 poor families in protected public areas as compensation for the environmental service of preserving these areas. There are plans to extend the coverage to 300,000 families, encompassing a broader range of measures, such as clean energy use.

South Africa’s Expanded Public Works Programme EPWP - (including programmes such as Working for Water) created 1 million work opportunities in its first phase (2004-2009). The second phase of the EPWP (2009-2014) set an ambitious target of creating 4.5 million work opportunities.

Equity considerations should have a central place in shaping and implementation policies for green growth. There must be a “Just Transition” ensuring that those likely to be negatively affected are protected through income support, retraining opportunities, relocation assistance, and other similar interventions.

Social dialogue is critical is all these aspects, to ensure that the voices of all actors and stakeholders are heard, and that structural transformations are owned by societies they are meant to benefit.

For more information on these issues and the ILO Green Jobs Programme please visit: www.ilo.org/greenjobs

Additional resources:

Filmer, Deon and Louise Fox, 2014, Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa Development Series. Washington, DC: World Bank

ILO, 2013, Sustainable development, decent work and green jobs, Report V. International Labour Conference, 102nd Session, 2013

ILO, 2012, Working towards sustainable development. Opportunities for decent work and social inclusion in a green economy (UNEP, ILO, IOE and ITUC)

ILO, 2011, Skills for green jobs: A global view

ILO, 2011, Towards a greener economy: The social dimensions

OECD, 2012, The jobs potential of a shift towards a low-carbon economy

The World Bank 2013, World Development Report 2013: Jobs