Karnataka, is the eighth largest state in India, with a geographic area approximately the size of Spain and population equivalent to France. Considered as one of the most progressive states in India, Karnataka has recorded impressive economic growth riding on a highly successful Information Technology sector. In 2014-15 Karnataka's agricultural sector posted robust growth despite a spate of successive droughts that crippled the economy.

Recurring droughts, increasing climate variability, and an inherent vulnerability due to a higher share of arid lands, have led to a growing demand-supply gap in food production and water availability for Karnataka’s growing population. A study by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) indicates that while the number of households is expected to increase at an annual rate of approximately 2 percent, the area under food grains is expected to decline by 0.5 percent between 2012 and 2017. The state depends heavily on groundwater rather than surface water for irrigation and consumption. Thus, Karnataka has the third-largest green water footprint (volume of rainwater consumed for crop production) in India. The writing on the wall is clear; climate change will be a force multiplier that will undo the state’s successes in achieving inclusive economic growth and poverty eradication.

Persistent droughts have forced the government of Karnataka to announce distress and crop failure for two consecutive cropping seasons in 2015-2016. Storage levels (as a proportion of reservoir capacity) observed in January 2016 in more than half of its reservoirs are lesser than half of the decadal average threatening power generation and irrigation.

Image 1: A parched field from chitradurga district, karnataka

The Green Growth strategy for Karnataka produced by Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) in collaboration with Bangalore Climate Change Initiative (BCCI-K) drawing up insights from a consortium of leading scientific research institutions and reputed policy think tanks, identified challenges posed by climate change and opportunities to overcome them. Micro Irrigation (MI) was identified as a high-priority green growth opportunity offering both, financial feasibility and policy congruence for the government.

Karnataka has realized the game-changing potential of MI technology in the agricultural sector. The state government organized a consultative workshop on micro irrigation in March 2015, which recommended the setting up of an empowered Working Group to draft Karnataka’s Micro Irrigation Policy. GGGI led an analysis that helped answer important policy questions for the successful design and roll out of the policy, including: estimation of real potential and investment costs for scaling up MI adoption in the state; targeting strategies for government subsidies to achieve effective service delivery; low-cost MI options for small and marginal farmers; designing appropriate institutional mechanisms for implementation and monitoring-evaluation systems for the government.

The Implementation Roadmap for Karnataka’s proposed Micro Irrigation policy, developed by GGGI distills important scientific, field research and policy insights into evidence-based micro irrigation policy for the first time at sub-national level in India.

The report recommends a paradigm shift in promoting MI as an income-enhancing technology rather than a water/energy-saving technology, boosting the attractiveness for adoption. The likely benefits include expansion in the irrigated area and cropping intensity, undertaking pre-monsoon sowing, saving labor, energy, fertilizer and other input costs, improving productivity and enhancing net farm incomes. According to records of Departments of Agriculture and Department of Horticulture, cumulative area of 0.9 million ha has been brought under MI ever since it was initiated in 1991-92 in Karnataka.

The study estimates the potential for Micro Irrigation (MI) in Karnataka in the range of 2.2-2.7 million Hectares of state’s Net Irrigated Area. Despite being a leader in MI promotion, the study finds that there are around 13 districts in the state that fall below the state average in adoption of micro irrigation technologies. The proportion of the area under MI to the Net Irrigated Area is lowest, at around 8 percent, for the socio-economically vulnerable, Eastern Dry Zone. Insights into vulnerability and public spending in agriculture will help prioritize climate resilience investments by the government.

To accelerate the adoption of MI technologies in the state, the study recommends an autonomous, single-window institutional system integrating best practices from leading states of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat. In comparison to the subsidy delivery mechanisms in Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka the report recommends reforming the state-run Micro Irrigation Corporation (KAMIC) with an empowered governing board chaired by the Chief Minister (or a senior cabinet minister) with representatives from key departments – industry, academia and financial institutions.

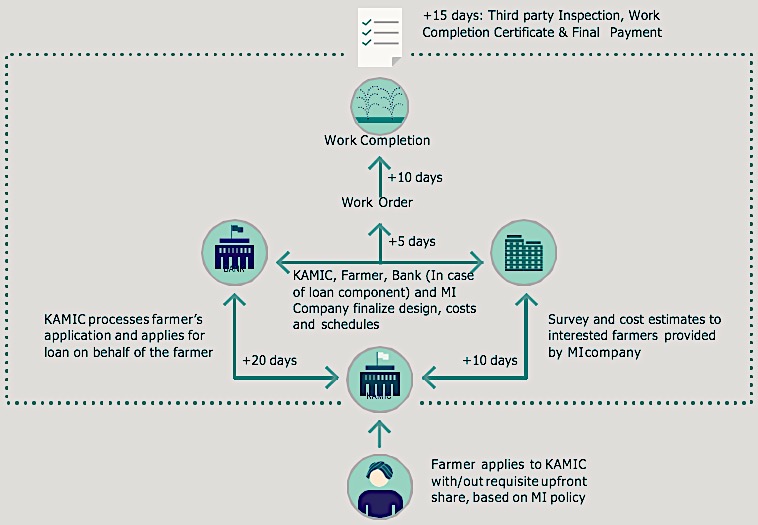

The subsidy delivery guidelines included in the report also recommend a time-bound application processing protocol where farmers get final installation done within 50 days of application and suppliers receive final payment within 20 days of final installation.

Image 2: Proposed MI service delivery model under single window system

For the first time, considerable focus has been placed on Low-cost micro irrigation technologies (LCMI) such as Pepsee tapes, and Drip tapes that are not covered by subsidies and offers the potential to be viewed as ‘stepping stones’ for first-time adopters and small and marginal farmers.

As adoption density in Karnataka increases, the system and servicing costs should fall and these gains should get suitably reflected in unit prices and passed on to the farmers, which is not the case today. Analysis indicates that the cost of large drip irrigation systems has been increasing at the rate of 7% per year, acting as an adoption barrier for small and marginal farmers. LCMIs allow farmers to experiment with a new technology at minimal costs and by encouraging ‘farmer-assembled’ systems and ‘demystifying’ the technology. The report recommends that it is important to encourage and support informal yet vibrant indigenous LCMI markets or innovation ecosystems in Karnataka.

Image 3: Low cost drip irrigation technology from Driptech

MI has also been positioned as an opportunity that can help the state government tap into domestic and international funds enabling expansion at lower costs to government. The opportunity is seen to be aligned with national and international climate financing opportunities including the “Green Climate fund” (GCF) and National Adaptation fund for Climate Change in India.

The report recommends an innovative, simple subsidy based on repeat adoption. The annual subsidy cost of government, in a business-as-usual scenario with 7% cost escalation, is expected to be in the range of INR 12500 million in 20 years assuming the full potential is covered.

Image 4: Micro irrigation promotion with plastic mulch in small holder farms of Karnataka

The study suggests that by fostering a healthy competition and developing a farmer centric MI market, even a three-percent annual reduction in unit costs could bring down the subsidy burden substantially. A robust and regular Monitoring and Evaluation System and Capacity Building Plan is recommended for ensuring full value for government money spent. Training and capacity building activities are recommended at three levels – farmers, field staff, retailers and dealers, and lastly, government officials and industry leaders.